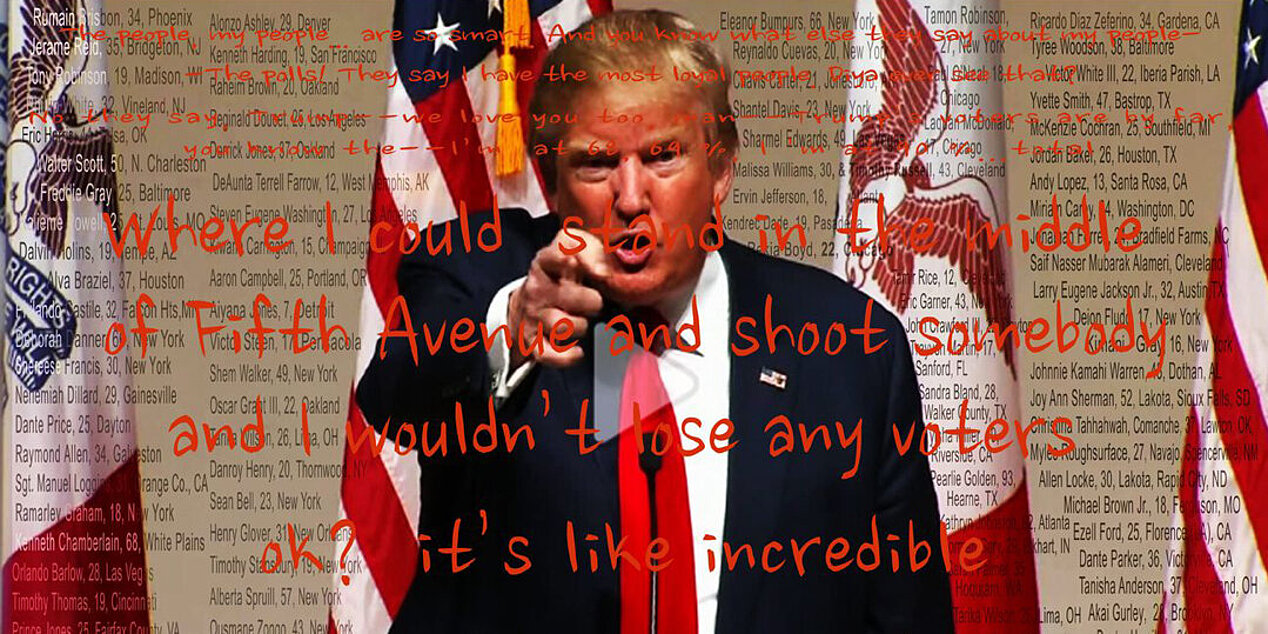

Contemporary populism has three key characteristics: One is an onslaught on the very idea of truth, facts and expertise. Populism is a form of epistemic democracy. „You don’t know better than we do“ is its motto. The second characteristic of populism is that it is an onslaught on establishment and on elites, whatever they are. Chavez or Trump or Bolsonaro or Salvini or Le Pen portray politics as rotten to the core by Illegitimate elites that are stealing or misusing taxes and public money, giving it to the wrong people, favoring global elites and European bureaucracies etc. Curiously, many of these slogans derive from people who have unfathomable wealth and privileges, as Trump.

Fear, Resentment and Pride

And third: Populism combines three emotional programs or lines of action: fear of immigrants, of decline, of China or of insecure futures; resentment presumably caused by the fact that working classes and many segments of the middle classes have been left behind and could see minority groups as women, African-Americans or LGBTQ groups gain in power and visibility; and pride, most notably but not only national and male pride which expresses the sense of humiliation which many men feel at having been outpaced by women.

Is there something wrong about these emotions? In her massive book Political Emotions Martha Nussbaum has tried to reflect on the nature of emotions we should privilege in democratic and liberal societies.[1]

Nussbaum moves away from the cliché that emotions should be banned from an adequate democratic and deliberative process but only to repeat other trite clichés: love and compassion are to be privileged; fear, shame, envy are to be banished from political arrangements.

Political Emotions

We may offer two objections. “Negative” emotions are so only from the standpoint of an object who finds them unpleasant or threatening. When viewed in structural terms, these negative emotions can be quite crucial to the maintenance of groups and social arrangements. For example, the 17th century political philosopher, Thomas Hobbes, suggested that “fear” was constitutive of the state of nature and was key to explain the social contract. More precisely, as Hobbes proclaims in De Cive[2], it is not mutual love between men that makes them enter into a social contract and civil society, but rather their mutual fear. Fear, then, is at the heart of the social contract and civil society, with the power of the state lying in its capacity to create peace which is nothing more than stopping to live in fear. Or to take another example of a negative emotion turned positive: In his Fable of the Bees[4], Bernard de Mandeville famously argued that greed and envy could generate positive social goods such as commerce and exchange. What made these negative emotions socially useful was their capacity to transmute themselves into a positive social good –economic activity, industriousness, competitive gain – which in turn created mutual inter-dependency and economic flourishing.

My point thus should be clear enough: what may perhaps be true for individuals, namely that “negative” emotions decrease their well-being, success, or capacity for love, may not be true for body collectives, as negative emotions play regulative roles in social life. Emotions then are not good or bad for society in the same way they are good and bad for an individual.

Unworldly Love

Let me take this point further: in the same way that fear, envy, or anger are not only destructive passions, but can organize social and political bonds love and compassion are not the right candidates for the formation of a good political bond. Nussbaum thinks that the purpose of the political bond ought to foster love. She suggests that: “ (…) society must preserve at its heart, and continually have access to, a kind of fresh joy and delight in the world , in nature, and in people, preferring love and joy to the dead lives of material acquisition that so many adults end up living, and preferring continual questioning and searching to any comforting settled answers.” [4] In her discussion of Augustine’s notion of agape, Arendt famously wrote against the role of love in political affairs.[5]If love was to play any such role in politics, Arendt claimed, we could never have the power to forgive or judge. Arendt went as far as suggesting that Augustine’s love is “unconcerned to the point of total unworldliness"[6] with our particularities, reminiscent of the indifference of agape. That is, because love does not enable the act of judgment, such love does not allow human beings to make up their minds on their own and to engage into what Nussbaum thinks should be at the heart of society, namely justice and fairness.

We are thus left with a philosophical problem: on the one hand we have the intuition that fear, resentment and pride are the wrong candidates for a democratic politics. On the other hand, the emotions proposed by Nussbaum simply do not reflect the nature of processes in liberal politics. Yet, what we may say with certainty is that emotions should no longer be banned from politics, with some proponents of left-wing politics even suggesting a left-wing populism that would not shy away from the use of emotions.

Useful Fictions of Progress and Rationality

Liberal and left-wing politics have been based on the useful fictions of progress and rationality. These fictions could guide the political imaginary of liberalism as long as industrial capitalism and nationalism seemed to deliver on their promises, that is, as long as they were able to expand the social covenant by integrating excluded social groups in economic production, providing them with the possibility of steady economic progress and the privileges accrued to national membership. As long as these useful fictions were aligned on a social order that seemed to accompany them, the notion of rationality and progress that were at the cornerstone of liberal states and nations could guide political rhetoric and speeches. But financial and global capitalism has created new lines of fracture which have undermined the plausibility of national membership, economic progress, or rationality as narratives for the self or for the collective.

Populism has been an emotional response to the rationality of classical liberalism: to its assumption that truth must prevail, that experts have a privileged status in establishing that truth; that enlightened discussion is the core principle of liberalism. Until it finds new useful fictions, liberalism and left-wing politics are well-advised to tap into the vast emotional reservoir of the disquieted citizens for whom capitalism or nationalism are no longer working, but not the emotional reservoir of fear and resentment. Liberal emotions have traditionally included indignation and compassion. It can also add anger and hope.

[1] Nussbaum, Martha C. Political emotions. Harvard University Press 2013.

[2] Hobbes, Thomas, and Carlo Monti. De cive. Vol. 2. Kessinger Publishing 2004.

[3] Mandeville, Bernard, and Phillip Harth. The fable of the bees. Penguin UK 2007.

[4] In: Nussbaum, Martha C. Political emotions. Harvard University Press, (2013:93).

[5] Arendt, Hannah. Love and Saint Augustine. University of Chicago Press 1996.

[6] In Arendt, Hannah. The human condition. University of Chicago Press, (2013:242).

About the author

Eva Illouz has been Professor of Sociology and Anthropology at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem since 2006. Her research focuses on the sociology of emotions, consumer society and media culture. Recent publication: Happycratie: Comment l’Industrie du Bonheur contrôle notre vie Premier Parallèle Editeur, Paris.